|

www.rhinoceros-group.com |

|

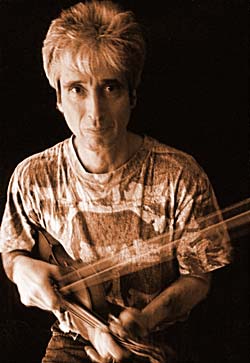

You're originally from Chicago, could we start by looking at your childhood and how you first got started in music? I come from a musically orientated family. Both of my parents were involved in music. Not professionally, but they both loved playing music. My mother played piano a bit and my father sang. My older sister is also quite an accomplished pianist. We always had a baby grand piano in the apartment. But I think the main influence was my uncles, my mother's brothers. They were both really amazing blues and jazz pianists. They didn't play professionally because they had other things going. One was a lawyer and the other was president of the Esquire Corporation. I used to play with them when I was a kid and it was really inspiring. There was also all this great music happening in Chicago which really turned me on.  You recorded a rare '45 for the Chess subsidiary label, Earic, in '63 when you were only 15 years old. How did this recording come about and were any other recordings made that have remained unreleased?

You recorded a rare '45 for the Chess subsidiary label, Earic, in '63 when you were only 15 years old. How did this recording come about and were any other recordings made that have remained unreleased?

When I was 14 or 15 years old I was writing a lot of songs. I had a band called The Tools for a while and we performed at a lot of clubs during this period. I also performed solo and as part of a duo. I was trying to find a record company and I met this lawyer who knew someone that was working for Earic Records. I went to play for him and he liked my songs. And that was it. I did this single as a duo with another guy called Don Czerniak and we called ourselves Michael and Lee. His middle name was Lee and mine is Michael. We did two more tracks that I wrote, "Break Away" and "I'll Be With You" at the same studios at Chess, but the deal never happened. They are really great and I have copies of them on acetate. The tracks have got horns, a funky rhythm section and a friend of mine plays harmonica which we decided to put a fuzz tone on. It was a lot of fun to make. I met Bo Diddley and all kinds of people at Chess. You have always been a prolific writer. Did anyone record any of your songs during this period? No, not at the time. Not many people have recorded my songs but I've had lot of near covers. A long time after that Ellen Mackelwain a great slide guitarist and singer on the blues circuit did cover one of my songs. At one time I had a hold on my songs. I had a lot of interest and really thought something was going to happen. Roger Daltry had one of my songs, which he was going to put on his first solo album. It was going to be the first single off it, but it never happened. Roberta Flack expressed interest in one of my songs and Blood, Sweat & Tears did actually record one called 'Money Can't Save You'. Little Richard was going to record one too and I thought, "boy, if only one of these things comes through it will be great."  The only one I know for sure that did get recorded was the Blood, Sweat & Tears track. When I played it for them, I said that it needed to be done in the old Wilson Pickett style, but they said, "no, no we know how we want to record it" and they ended recording it three times! It was never right. I have a recording of the song that I did and it's great. I used the O'Jays' backing group. I couldn't come to an agreement with the producer who recorded it and, unfortunately, it was shelved.

The only one I know for sure that did get recorded was the Blood, Sweat & Tears track. When I played it for them, I said that it needed to be done in the old Wilson Pickett style, but they said, "no, no we know how we want to record it" and they ended recording it three times! It was never right. I have a recording of the song that I did and it's great. I used the O'Jays' backing group. I couldn't come to an agreement with the producer who recorded it and, unfortunately, it was shelved.

I believe that you studied at the Roosevelt University during the mid-'60s. Could you tell us more about your time there? I was finished with high school and decided to go to university which was expected of me. I wanted to major in music. I had studied music as a child, but not really formally. I was never happy with the formal way that music was presented and taught. Even today I don't like it. I started learning classical piano in my last two years in high school with this professor from Roosevelt University. It was a highly respected school throughout North America. The famous pianist Van Clyburn, who went to the Soviet Union during the Cold War and won the Tchaikovsky competition, studied there with one of my professors, Rudolf Ganz. I studied there from late 1965 through to the summer of 1967. In fact, I quit to join Rhinoceros. I left one semester before I got my bachelor of music. Who were your main influences at the time as a singer and as a composer? I was really into all kinds of stuff. I really liked Muddy Waters and Otis Spann, who was one of my favourite blues pianist. I was also amazed by the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and Cream. I loved jazz too, people like Oscar Peterson and Ramsey Lewis. I have to say that classical stuff was always work for me. I was always anxious playing classical concerts, even though I was doing quite well. Rudolf Ganz wanted me to be a concert pianist. He said I had what it took to make it. He was an open minded man who also really enjoyed my own personal compositions. When I decided to leave school and join the group, later to be known as Rhinoceros, the draft was happening. I had a student deferment and I remember having a conversation with Ganz, telling him that I had this chance to go and be part of a project that was going to have my music at the centre of it, and it was something I was really excited about. He completely reaffirmed my gut feelings about it and told me to go where my heart was. He was a big influence on me. How did Paul Rothchild hear about you? That was quite a story. My girlfriend at the time, Katie, went off to New York University to study film. I was doing my thing in Chicago and we saw each other whenever we could. Without my knowledge, she had a friend who wrote for either Billboard or Cashbox and she told him that I wrote songs and sang. It turns out that he knew Paul Rothchild quite well. Paul was always interested in finding fresh talent. This guy asked Katie if I was really good and she said, "he's really great", so then he said, "well, he'd better be because I am going to tell Paul that I've heard him and he's really great." And that's what he did. My first morning after arriving in New York, Katie told me I had an interview at one o'clock with this producer called Paul Rothchild, who I'd never really heard about before. So I went over and played for him, he really like my songs, my singing, and the one song that really knocked him out was "That Time of The Year". I remember he kept calling people in to the office to listen to me play. He then said: "What do you want to do? I want to record you as a solo or you can join this super group that I am putting together". He told me about all these great people that he had got together for this group that turned out to be Rhinoceros. I thought the project was really interesting and said the group sounded great to me. It was unreal too. There I was sitting in Elektra Records and this guy says he wants to produce me. When I walked out I still couldn't believe that something was going to happen, but Paul was really nice and friendly. He said that he would call me soon and he did! He called me a few days later in Chicago, asked me what I thought and I said I was going to quit university and be part of the band. |

||||||

What were your initial impressions of the auditions that led to the formation of Rhinoceros?

When I first arrived at Paul's house in California, there were all these people. I don't know, maybe 12 or so. These were the people who were the possibilities for this group. There was a real variation of musicians. There was a guitar that was being passed around and people were playing their songs. I knew something was going to happen because there was a big investment in time and money. I also knew that the interest in me was genuine because they had paid for my flight out there and were putting me up. Paul had also expressed interest in me without the group. At that point I never felt threatened. Nobody was ever asked to leave. I don't know if you knew that? People just said, "this isn't for me".

In fact there were two groups that came out of the auditions. It was a very strange situation. The first meeting there was John, Doug, Peter (Hodgson) and myself. At first, John was very quiet. He didn't sing that much and I was really surprised when I found out who he was. A lot of the people there felt an incredible pressure to the point where they said, "I'm out of here!"

Can you tell us more about the recording of the group's debut album? I believe that a lot of your songs never made the final track listing.

There were some really magical moments and there were some very difficult times. I hadn't done much of that "corporate rock" stuff before and I found it trying. Even after all the auditions, it wasn't like water off a duck's back. There was a lot of pressure from the whole package and that ultimately led to Jerry Penrod's departure. He couldn't take it anymore, which was tough because he was a great bass player and everyone really liked him.

The songs of mine that didn't make it on either the first or second album could have been some of our breakthrough stuff. Not only that, but some of the most artistic, creative and original, off the wall, funny with a real social statement material that were really works of art were cut because Elektra wanted to push this heavy rock band. That is eventually why I left the band. John also felt this way. He thought that this material was really soulful and unique and would have been a good direction to pursue. There were lots of songs that we recorded that never made it - "It's a Fine Day For Loving You", "You're The Way", "Horace The Rhino" and "Nothing To Say". One song, "It's A Sin to Take a Life", I still play to this day. In fact, I might put this on my next album.

The songs of mine that didn't make it on either the first or second album could have been some of our breakthrough stuff. Not only that, but some of the most artistic, creative and original, off the wall, funny with a real social statement material that were really works of art were cut because Elektra wanted to push this heavy rock band. That is eventually why I left the band. John also felt this way. He thought that this material was really soulful and unique and would have been a good direction to pursue. There were lots of songs that we recorded that never made it - "It's a Fine Day For Loving You", "You're The Way", "Horace The Rhino" and "Nothing To Say". One song, "It's A Sin to Take a Life", I still play to this day. In fact, I might put this on my next album.

There were also things that we didn't record like "Purple Pigeons" which the band played incredibly. Another one was "Storm" which was really poetic and original. There was another one we recorded called "Once Again" that was seven/eight time signature and was really, really beautiful. Billy Mundi showed me a lot about using different time signatures and added very much to that piece.

So it was the "hard rock" direction that led you to leave the band for a solo career in 1969?

It wasn't just that. What I was striving for in my compositions was the place I felt we should go, at least in so far as the creativity and originality. A lot of songs were getting cut from the albums that I really believed would have been great for the band's direction. In fact, I was so turned off by the whole thing, I was going to quit music professionally when I left and find something else to do. I was really fed up that I wasn't going to be able to express myself creatively. Immediately after I left Rhinoceros, my wife and I got a volkswagen camper and drove to California. We eventually ended up in San Francisco where my sister and some good friends lived.

How did you get back into playing and forge the deal with Shelter Records?

I was out one evening with my sister, my wife and some friends in this lovely little bar called the Ribble Tad Vorden and there was this piano on stage not being played. They kept on bugging me to get up and play until finally I did. I think I played "Big Bad Momma", which I had written when I was 15 years old. The people in the club loved it, so I kept playing and pretty soon I was really enjoying myself. I started playing solo in clubs across San Francisco and I started writing songs again. Before I knew it, I was trying to hustle up a solo deal and I got one after meeting Denny Cordell. At that time you could walk into any record company and play for the president. I remember played for loads of people like Herb Albert, but they kept on saying, "we'll bring it up at the next board meeting". I played a few songs with Denny and he said, "I love it. Let's do something", no meetings or anything, just straight to it.

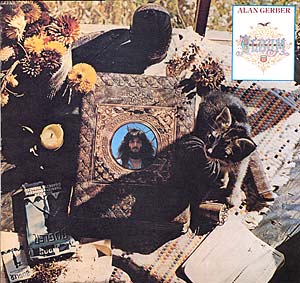

The Alan Gerber Album (1971)

|

|

I noticed that you used Michael and Danny on the album sessions. Can you tell us about the recording of the Alan Gerber Album?

We did that album in Memphis, Tennessee and Steve Cropper was one of the engineers. I recorded at Dan Penn's studio first and unfortunately that got erased. That's quite a story. We had just a few days in the studio; we found some players and did some tracks that we liked. We had three basic tracks that we were going to keep right? Denny and Dan (along with their buddy Jack Daniels) had those three on a reel of tape and we were going for a fourth. Not only did we not get that track but also they inadvertently erased the other three. I was really mad. I couldn't believe that something we had worked so hard to get was lost in such an irresponsible manner.

Denny said he had to go away for three weeks but when he got back we could start again. I said, "I don't want to wait three weeks or a month, I'm ready to produce myself". He said okay and got me back in the studios at TMI the following week, which is where I met Duck Dunn, Al Jackson and Steve Cropper. He had great people for me to work with and I started it without him. We were talking about people we were going to use. He wanted to put some big names on the album. Dave Mason was supposed to play some lead guitar and Leon Russell was going to put on some hammond organ. But I love the way Michael Fonfara plays organ. He knows me and he knows what I like. Let's just say, I could have had all these big-name people play on it, but I was only thinking about going for the quality of what I wanted.

Denny said he had to go away for three weeks but when he got back we could start again. I said, "I don't want to wait three weeks or a month, I'm ready to produce myself". He said okay and got me back in the studios at TMI the following week, which is where I met Duck Dunn, Al Jackson and Steve Cropper. He had great people for me to work with and I started it without him. We were talking about people we were going to use. He wanted to put some big names on the album. Dave Mason was supposed to play some lead guitar and Leon Russell was going to put on some hammond organ. But I love the way Michael Fonfara plays organ. He knows me and he knows what I like. Let's just say, I could have had all these big-name people play on it, but I was only thinking about going for the quality of what I wanted.

And I knew that there was nobody who could play like Danny (Weis). He was amazing and understood exactly what I was going for. It was really funny. The first time Denny and Leon ever heard Danny play was for a session in Leon's house in L.A. before we went back to Memphis. We were trying to do some tracks and Danny lived in L.A. at this time. They wanted to use Dave Mason and I said, "I want you to hear this guy called Danny Weis, he's amazing. There's nobody like him and this is the guy I want on my album, and when you hear him I think you'll know why". And they were both sort of like "well, yeah okay".

So I called him and you know "Sigmund Blues" from my album? We were doing the rhythm track, Danny came in and he had never heard it before. The first time through, Denny and Leon's jaws just hung (laughs), they couldn't believe how good this guy was. He had never heard this song before! And then Danny came to listen back to what he had done and he said: "I think I am getting the idea of this song" (laughs). They thought that was great. Danny said, "let's try it again" and he did something completely different but it was just as mind boggling. He came back and listened to it again and they just couldn't believe it. He did it a third time and it was just as incredible and then when he came back in to listen he said: "I am sorry, I am really not into it, I just don't feel comfortable. I don't know what it is, I just don't feel right at this moment, please excuse me". And he left (laughs).

Denny and Leon agreed that this was the guy for the album. When it came time to do the organ, I called Michael who was living up in Toronto at the time and he came to Memphis and he put on the organ. For a short time I had both Danny and Michael in my band and we did some shows. We opened for Leon in huge auditoriums and did some clubs in New York. This would have been 1970/1971. It was great because this was after Rhinoceros and there was no hype or heavy corporate pressure. Unfortunately, there was also no distribution, but we did have a lot of fun.

After the Shelter album you ended up moving to Quebec and released a rare single on the Good Noise label. What did you get up to in the intervening years and what motivated you to move to Canada?

After the Shelter album you ended up moving to Quebec and released a rare single on the Good Noise label. What did you get up to in the intervening years and what motivated you to move to Canada?

Actually, I had left California because my wife's family was back east. And while I was on tour with the Shelter album, she wanted to be closer to her family. So we moved from Mendocino, California, a beautiful little place by the ocean, to a little farmhouse in Vermont. That's when Frazier Mohawk was in Montreal and he was working with a producer called Andre Perry. They were finishing up an album for a duo called Jackson & Hawkes, they needed some Appalachian fiddle on a couple of tunes and that's exactly what I could do on the fiddle at the time. So Frazier called me and said, "why don't you come up here and put some fiddle on the tracks?"

So I went up to Montreal for a wonderful experience. I was in the old part of Montreal and nobody spoke English and I didn't speak French at the time. It was like I had a fish bowl on my head (laughs). People were so nice and friendly. It took me a really short time to add some fiddle, maybe fifteen minutes for each song. I also played some of my music for Andre Perry, who really liked it and ended up producing the "Tied On" single.

One night at the hotel across the street, a place called the Hotel Nelson, a friend of mine, Lewis Furey, was playing for people and they were really loving it. He saw me in the audience and said: "Alan, why don't you come and play a few songs on this beautiful piano?" I did and people went nuts! When I finally got off the stage, the manager asked me if I would play there, two weeks straight, six nights a week. He put me up at the hotel a week before I played for free. It was great! There were line ups around the corner and I started playing other places. After making many more Montreal contacts, splitting up with my wife, living on and off in New York, I eventually moved up to Montreal.

Did you record any other songs during this period that weren't released?

Did you record any other songs during this period that weren't released?

Yeah, I did "Money Can't Save You" and another one called "Happy Now".

You also got involved with Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue.

I was playing in Quebec City when they were coming into town. Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez had gone out to have a beer at a place that I was playing at. I was with Jim Zeller, the harmonica player who plays on the "Boogie Man" CD. They came in, heard us and said, "hey, you must play on this revue". It was an offer I couldn't refuse! Two of my songs are in the film "Renaldo and Clara".

What were the songs called?

One is called "Chanson D'amour" and the other is an instrumental called "Shores of Venus". "Chanson D'amour" is playing at the part when Allen Ginsberg is making love to someone (laughs). He came up to me afterwards, gave me a hug and said: "That's my favourite song in the movie" (laughs). It was nice to get a hug from Allen Ginsberg.

After the Good Noise single, you seemed to have maintained a low profile for a while. Presumably you were still playing?

I was always playing and ready. But do you know what it was? I was waiting. One part of me didn't want to get involved with the big industry machine. I didn't want people changing what I wanted to do. I was sick of all the bullshit and all these people who were lying to me. Another part of me needed an outlet. So I was shopping around to find the right deal. Someone who would release my stuff but allow me to do what I wanted to do. I was really having trouble finding the right pieces to put the whole puzzle together. So finally, it was my present wife who said: "Why don't you just record it on your four-track? You know how to make it sound real good". I said "I will", and I did. I mastered on a DAT. And that album, "The Chicken Walk", is being played on blues shows all over the world and ever since I have been putting out a new CD every couple of years.

You have been very prolific in recent years, releasing a string of CDs over the last four years. Were these songs that you had built up over time or did the songs come to you quite quickly?

You have been very prolific in recent years, releasing a string of CDs over the last four years. Were these songs that you had built up over time or did the songs come to you quite quickly?

Some of the songs were songs that I had written a long time ago and rewrote. A lot of them were new. I go through periods where I am really prolific and other times when I am busy with other things. I have been writing a lot with Rolf Kempf. He's a wonderful poet/songwriter who is best known for his Alice Cooper hit "Hello, Hurray". We have been writing a lot over the internet because he lives so far away in British Columbia and the telephone gets way too expensive!

Your three CDs, 'The Chicken Walk', 'Fools That Try' and 'Boogie Man' all vary tremendously in presentation and content. Could you tell us more about these recordings?

For "Fools That Try", somebody lent me a DR8, an eight-track, direct to hard disc machine. I had some other musicians and brought the production quality up a bit. And then the "Boogie Man", I did through a PC. Everything went through tube pre-amps to warm up the sound. It took me a lot of time, cost a lot of money, but it is an album that I'm quite proud of. A very talented friend of mine, Richard Belanger, helped me mix "Chicken Walk" and "Fools That Try". He also co-produced, engineered and played guitar on "Boogie Man".

The new album you're thinking of doing. Is it going to be along the same sort of lines as the "Boogie Man"?

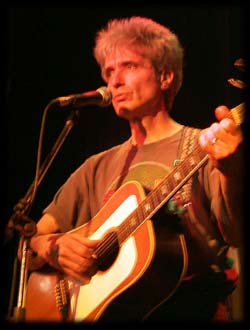

The new album, which I am now in the process of making, is a live solo approach using the best takes from numerous concerts.

Any plans to work outside North America?

I'd loved to play in Australia. They play the "Boogie Man" quite a bit on the blues stations over there. I'd also love to come and play in England. I used to live and tour in France. If I had the opportunity to do a compact tour of France again where I could bring the family, that would be great. I would go by myself if it was two weeks or less, but I am not interested in anything that would keep me away from my family for long periods of time.

What is your fondest memory and biggest regret of the Rhinoceros days?

What is your fondest memory and biggest regret of the Rhinoceros days?

I'll tell you what it was. This was a prolific time for me and I was writing lots of off the wall, original material. My fondest memory was seeing how these guys could interpret and play these creations that came from the wildest depths of my imagination. That was, by far, my fondest memory. My biggest regret goes hand in hand with my fondest memory. Most of the truly original and groundbreaking compositions of mine were kept off the albums (by the record company) because it didn't fit with the corporate "heavy horny beast" image. After two albums, I realised that I needed to go and do something else. C'est la Vie!

Alan, many thanks for giving up your time to speak to us. Good luck with the "Boogie Man" and keep us up to date with your touring plans.

Thanks, nice speaking to you.

Related Links:

www.alangerber.org

Official site, with biographies, reviews, and purchasing details for Alan's solo albums: Chicken Walk, Fools That Try, The Boogie Man and his latest, Blue Tube.

| Alan's albums are available from CD Baby, http://cdbaby.com/ |

www.bignoisenow.com/gerber.html

Has real audio samples from 'The Boogie Man' and some information about Alan.

|

These albums are now available: (details at www.alangerber.org) |

|||||||

| Chicken Walk (1994) |

| Fools That Try (1997) |

| The Boogie Man (1999) |

| Blue Tube (2005) |

Copyright © Nicholas Warburton/Alan Gerber. August 2001.